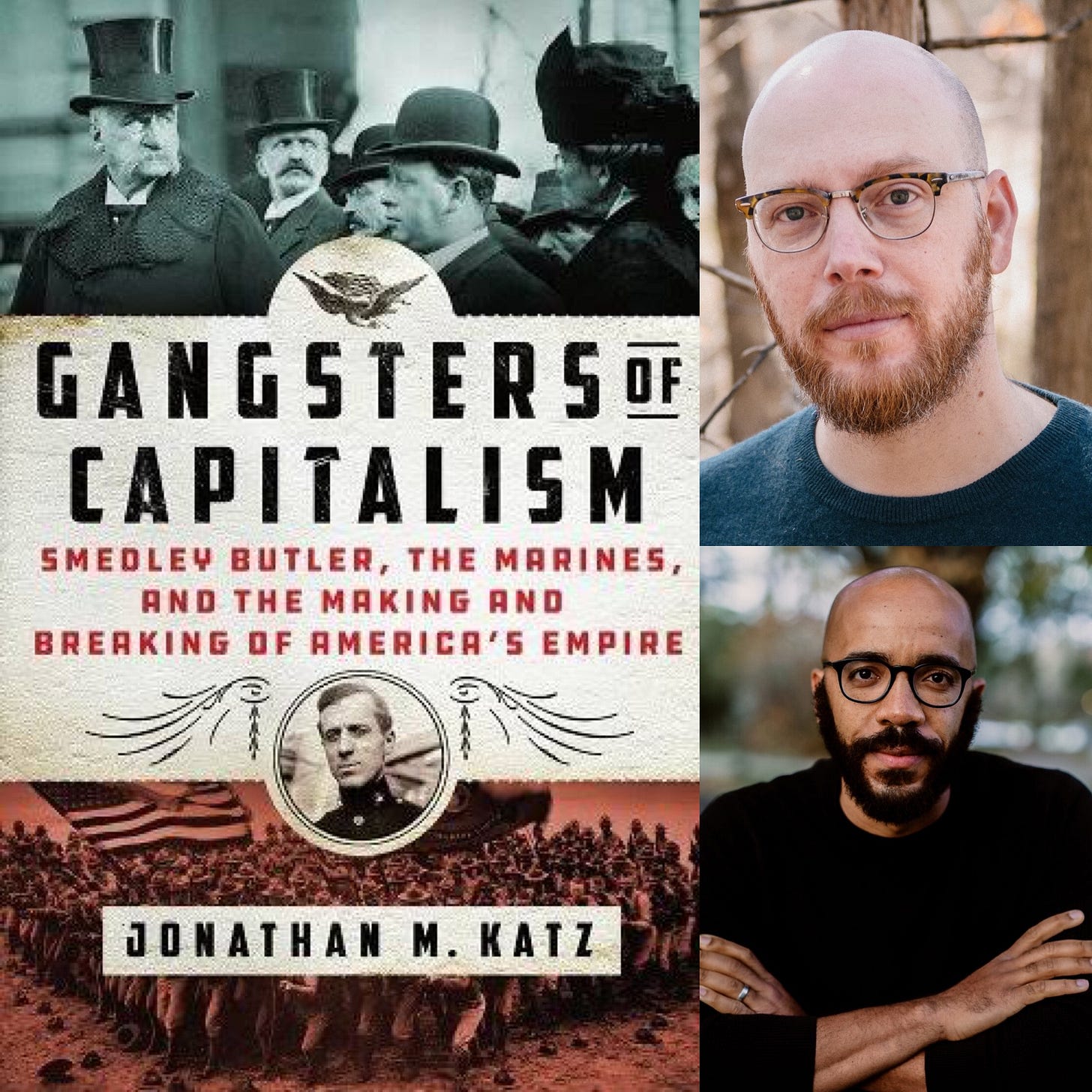

Folks, the day has arrived: Gangsters of Capitalism is in the world. You can find it at your local bookstore. If you order it online, it will be shipped or appear in your e-reader or audiobook app immediately. Hallelujah. Oorah.

Elsewhere, things are rougher. Russia looks poised to invade Ukraine. Voting rights are in deep peril. The pandemic is … well, you know. At moments like this, it can be tempting to look back to earlier moments of crisis for inspiration and comfort—only to find our forebears did the exact same thing, by looking back to their past for examples to follow.

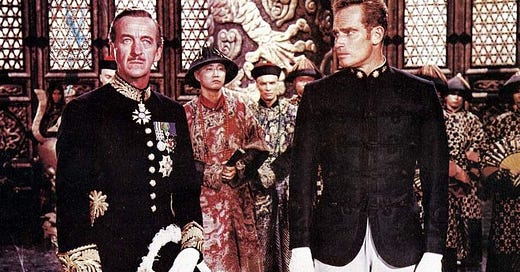

This week’s Gangsters Movie Night is 55 Days in Peking, Nicholas Ray’s 1963 film about the Boxer Rebellion, starring Charlton Heston, David Niven, and Ava Gardner. Stylistically a Western, it is set in the China of 1900, during the invasion in which the Marines and Smedley Butler took part. But the messages of internationalism, the fears of imminent world war, and the overriding theme of civilization vs. barbarism are straight out of the high Cold War in which it was made.

My guest is Jeffrey Wasserstrom, a professor of modern Chinese history at the University of Calfornia, Irvine, and author of the upcoming book, The Ghosts of 1900: Stories of China in the Year of the Boxers. It’s a great conversation. Please enjoy and share widely. A transcript is below.

For more on the real Boxer War and how memories of the U.S. role in that invasion shape Chinese policy today, you can also check out this abridged excerpt from Gangsters that just went up at Foreign Policy.

And be sure you’re signed up for The Racket so you don’t miss the next episode when it drops:

Meanwhile, I’ve been busy with the Gangsters launch. If you missed my launch event at Politics & Prose with Mike Duncan, don’t fret—you can catch the replay here.

I’ve also been making the rounds of other people’s podcasts. Highlights include my interviews on DeRay Mckesson’s Pod Save the People, Jared Yates Sexton’s Muckrake, and Michael Issikoff’s Skullduggery. Some other big names to come.

I’m glad to report the reviews are stellar so far. I’ve most appreciated the raves from my former comrades at the Associated Press and this one from a Marine veteran at Task & Purpose.

And my next virtual bookstore discussion will be hosted by New America and Solid State Books. It features me in conversation with Clint Smith, the Atlantic writer and author of How the Word is Passed. I expect we’ll dive into our books’ shared focus on sites of memory and the silencing of the past. That will be on Jan. 27 at 12 p.m. ET. You can register and find more information here.

Episode transcript (may contain transcription errors)

Movie Narrator: Peking, China, the summer of the year 1900. The rains are late. The crops have failed. A hundred million Chinese are hungry and the violent wind of discontent disturbs the land. Within the foreign compound, a thousand foreigners live and work. Citizens of a dozen far-off nations …

Jonathan M. Katz: You're listening to The Racket, a podcast and newsletter that you can find at theracket.news. I am Jonathan M. Katz. It is pub week for my book Gangsters of Capitalism, Smedley Butler, The Marines, and The Making and Breaking of America's Empire. It's an exploration of the hidden history of America's path to global power and the ways that all seems to be crashing down around us today. Told through historical memory and the life of one of history's most fascinating but not well enough known figures, the Marine Major General Smedley Darlington Butler.

Gangsters is getting nice reviews from all over the spectrum. The Federalist called it “immensely readable.” Yes, the Federalist. Noam Chomsky calls it “a real page turner,” so there you go. Please go buy it and hit me up at @KatzOnEarth on Twitter to share your photos of the book in the wild. Stay tuned to the end of this podcast and I'll talk about some upcoming events for the release.

This is our second episode of Gangsters Movie Nights. So, each episode we're featuring a different movie that explores a theme or place from the book. Last time I had on Spencer Ackerman to talk about Harold and Kumar Escape from Guantanamo Bay. Not a great film, but it made for a great discussion. Check it out at theracket.news or wherever you get your podcasts.

This week we are moving actually across an ocean and a half, I suppose, to China, with 1963’s 55 Days at Peking. It's a war movie, although stylistically it's more of a Western, about the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. A war almost entirely forgotten by Americans, well remembered by people in China. However, it's covered in Gangsters and of course, Smedley Butler and the Marines took part.

So, this movie stars Charlton Heston as the Marine major, David Niven as a British diplomat, Ava Gardener as a disgraced Russian Baroness. It was directed—officially—by Nicholas Ray who is best known for directing James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause. It's kind of a weird movie, entertaining in parts, just cringey in others, not least because the main Chinese characters are played by white British and Australian character actors in yellowface, and it was a flop at the box office, but I think, like Harold and Kumar last week, it holds an interesting place in cultural memory, and is going to be a great jumping off point to talk about a lot of different issues.

So, to do that, I have a special guest, Professor Jeffrey Wasserstrom. Jeff is the Chancellor's Professor of History at UC Irvine, where he also holds courtesy appointments in law and literary journalism. His most recent books are Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink, and he's the editor of The Oxford History of Modern China. He often contributes to newspapers, including the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, literary reviews, magazines, The Nation, Dissent, The Atlantic, a whole bunch of other places. And he's currently finishing work on a new book, appropriately, The Ghosts of 1900: Stories of China in the Year of the Boxers. Jeff helped me a lot in preparation for my research in Gangsters ahead of the month that I spent reporting in China for the book. And he turned me onto this film at that time, and I'm really glad to be talking to him about it today. Jeff, welcome to The Racket.

Jeffrey Wasserstrom: Thanks, I'm glad you're glad I got you to watch this movie, even though parts of it are, as you say, very cringe-worthy.

Jonathan: All right, so here's how we're going to do this. Because this is a movie that no one—very few people—in 2022 have heard of, about a historical event that most people listening to this, in English in the United States especially, have not heard about, I'm going to give a very, very brief summary of the plot of the movie. And then, Jeff, I'm going to ask you to give a brief summary of the Boxer Rebellion, or the Boxer Crisis, as I believe you prefer to call it, so everyone knows more or less what we're talking about, and note that this is going to spoil the entire movie. So, if you want to watch it, it's on YouTube for free, hit pause, come back when you're ready.

All right. So, as I said, this is a Western, specifically a fort movie, except instead of Fort Apache being surrounded by menacing Native Americans. It's the foreign legation quarter in Beijing surrounded by menacing Chinese people. The movie opens with a long overture, there's some setup about how there's a big drought in China that foreigners are taking advantage of the crisis to seize more land and resources. Charlton Heston playing Marine Major Matt Lewis rides in on a horse leading a column of Marines who all look especially like cowboys.

He has a brief showdown with some Boxers which ends with an English missionary dead and a Boxer killed. Things keep getting worse between the Boxers and the foreigners until the Empress Dowager of China played by Flora Robson decides to ally with the Boxers to drive the foreigners out. The foreigners want to leave but David Niven as the senior British diplomat convinces everybody else in the legation quarter to stay. The Boxers kill the German Minister while another Chinese official played by another white guy looks on.

Then basically, there's a long siege, a couple of battles, and pretty impressive special effects for 1963. Charlton Heston and David Niven go on this weird raid dressed as Boxers to blow up the Chinese armory. A lot of people die bloodlessly, like they just kind of like fall over. And then finally, the cavalry arrives in the form of reinforcements from the eight-nation allied armies. There's also this weird romantic subplot involving Ava Gardner as this disgraced Russian baroness whose husband killed himself because she had an affair with a Chinese man and she and Charlton Heston kind of fall in love and then she dies and he doesn't really care. The movie ends with Charlton Heston riding off into the sunset with the half Chinese half Anglo-American teenage daughter of a Marine who died during the movie with the implication that Heston is going to raise her as his own daughter.

So, Jeff, why don't you take us through what actually happened briefly, more or less, in 1900 and explain what is the history that this movie is awkwardly, and often wrongly, trying to tell?

Jeffrey: So, the Boxers believe that the world had been thrown out of whack by the coming of what they saw as a foreign religion in the form of Christianity, and foreign objects, including railways and telegraphs and things like that. And so, there was a terrible drought and they blamed the drought in part on local Gods withholding rain to show their displeasure at the presence of these polluting foreign presences on sacred soil.

So, one thing that the movie leaves out is it most of the people, the Boxers attacked were Chinese Christians. And so, most of the violence was directed against Chinese Christians in the late 1890s. And the first foreigner they killed, they killed a missionary at the end of 1899. But then it became a global crisis, and the world became more invested in what was going on there, when they started attacking more missionary families.

And then they converged on Beijing, the capital of the Qing Empire, and also the nearby city of Tianjin. And they ended up putting both those cities under siege, threatening the lives of foreigners from many different places in those two cities. I don't like to call it the Boxer Rebellion because they weren't rebels. They talked about being loyal to the Qing Dynasty. Rebels traditionally in China tried to overthrow a dynasty. But instead, they claim to support the dynasty in standing up to foreign powers who had been bullying the dynasty and foreign powers have been carving out zones of influence and even claiming parts of Chinese territory for decades before that. First the British, but then the French as well. And then other countries, [such as] Japan, got in on the action as well.

So, the movie takes up at this point where what had been an uprising in rural North China has become an international crisis in two major cities of North China. And the focus is on Beijing, which makes sense, that's where the diplomats from around the world were. And so, it really made it an issue that led to the formation of this incredibly cosmopolitan, eight-[nation] allied army, which was, there had been alliances of powers in wars before, but usually they were just groups of European powers.

This constellation included for the first time—and this is what's crucial to your book and where your book captures this very well—American forces[, which] are kind of a major part of this joint imperialist effort, as it's seen in the perspective from China. And there's a lot to be said for it. These are a group of foreign powers who have designs on maximizing their access to the Chinese market, and also ideally to get sort of beachheads of one kind or another, their former formal possessions or at least parts of cities that they can have beachheads in.

And so, there are eight countries involved in this what becomes a war, and it's often called the Boxer war. Japan is part of it, Russia is part of it, the Western European powers, you kind of expect to be part of it, and the United States. So, it really is quite extraordinary. And then, there is the 55-day siege of Beijing, that's eventually lifted by the coming of an international relief force. So, it's strange because they focus more on the actions by groups within delegations. Whereas in a sense, the main action that decides the war is this foreign force that fights its way first to Tianjin and frees the captives there. By the way, captives there included a future President of the United States, Herbert Hoover, and his wife, who I think is a really extraordinary, a wonderful character in her own right, Lou Henry Hoover, who I actually devote a chapter to in my book.

Jonathan: And it should be noted, by the way, and this is in Gangsters, but Herbert Hoover gets conscripted by the Marines—by Littleton Waller and Smedley Butler's unit essentially—to guide them into the battle of Tianjin and Herbert Hoover is singularly responsible for getting Smedley Butler shot in the leg for the first time that he's wounded in action, which is something that Smedley Butler remembers later on when Hoover becomes president in the late 20s and early 30s. But anyway, I didn't mean to...

Jeffrey: No, no. That's really interesting. I mean, so Lou Henry Hoover tried to write a book. I related to her when I was writing my book, because I started worrying that I would never finish the damn thing, and I have, I know I'm close enough now that I can talk about it as being finished. But she worked on a manuscript for decades after that. She kept refining at about their experiences during the siege and she never published it. So, I was kind of haunted by that idea. But she sometimes would write letters, people would write letters to her about the stories about what she and her husband did during the siege. And apparently, there were stories about her husband being like a leader of the military forces inside Tianjin. And she would write back letters saying, "No, we didn't really do anything, all that heroic during it." But yeah, it was really interesting, but she kind of tried to demythologize some of it. So, I love that idea by the First Lady de mythologizing the heroism of her husband.

Jonathan: Well, one of the things that's interesting about this movie, 55 Days at Peking, it's the result of, at that point, 60 years of game of a broken telephone. And it's interesting to note actually, by the way, that it's been almost as long now since this movie came out as it was between the Boxer crisis and the release of this movie in 1963. But it's this very kind of fever dream, half remembered version of the events of 1900. So, as you note, the movie, it takes place almost entirely, I think, actually entirely within the legation quarter in Beijing, which is its essentially the embassy district. It was right next to the Forbidden City, which was the seat of the Qing Dynasty and the Imperial Palace.

And as you said, there was a siege. The diplomatic personnel were trapped in there for 55 days, but none of the big battles that happened in this movie happened in real life. It seems like this movie is kind of grabbing bits and pieces. There's a memory of big battles, but the real big battles were like Tianjin, where Smedley Butler was fighting his way into up the canal to Beijing. There were rumors and I talked about this a lot in Gangsters because they very much helped informed what Smedley Butler and the other Marines were thinking. Butler was 19 years old at the time.

There were all these rumors of these Boxer atrocities, the Boxer horrors that they were killing all the white people that they could find, they were crucifying white women. And Charlton Heston says in this movie, he says to David Niven at one point, "They're coming here and I just came from Tientsin, and they're killing every white man they can find." And that's not true, it was what the foreigners thought was happening, but it was actually an exaggeration. And this movie is, sort of, it is repeating the exaggerated version that it come down to the filmmakers as opposed to any sense of what actually happened in 1900.

Maj. Matt Lewis (Charlton Heston): I have just marched 70 miles from Tientsin. There are Boxers everywhere. They're killing every white man, especially missionaries, and every Chinese Christian they can find. And the Imperial Army isn't lifting a finger to stop them.

Sir Arthur Robertsen (David Niven): The Boxer bandits have been with us for years, Major. It could be that you're unnecessarily alarmed.

Maj. Lewis: Well, the next time I see some bandits murdering an English priest, I'll try not to be alarmed.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah. I mean, there were terrible murders committed by the Boxers, but the biggest murders were of Chinese villagers. The great tragedy of 1900 is the main victims of violence throughout were Chinese villagers first being killed by the Boxers if they were Christian villagers. I don't call them converts because actually some of them were Chinese Catholics from families who've been Catholics for generations. But the Boxers killed both Protestant and Catholic Chinese, and they did kill, there are some terrible atrocities of missionary families. But then, what happened was after and this is what's crucial is the movie, the credits roll, and this is in many of the Westerns tellings of the story, in books symbolically, the credits roll after the sieges are lifted.

But after that there were a whole series of atrocities committed by the foreign troops in China as acts of revenge as well as to suppress any possible future Boxers. But there were also rumors that were just unfounded of a wholesale massacre of all the foreigners in Beijing, and Beijing was cut off from telegraphic communication for a couple of weeks. So actually, there's this very dramatic period, during the summer of 1900, when people around the world were pretty sure the rumor circulated that the streets of Beijing had flowed red with foreign blood. And there were things like there was a planned mass funeral to be held at St. Paul's in London, for basically the character that David Niven plays, and his wife and children who were imagined to have been part of this massacre. And then when news came that, hey, actually, they're all still alive, they didn't actually cancel the funeral. They postponed it. Because the idea was, it could still happen.

And in the United States, there were a lot of stories about diplomats and their families who were believed to have been killed. And so, stories ran in the newspaper that look like obituaries with pictures of them. And there were plans for a funeral for Edwin Conger and his wife, Sarah Conger, and other Americans who were killed, and that too, that had to be canceled, or in that case, they said, "Well, let's take our plans for their funeral. And since they're not dead, let's start planning for their triumphant welcome home." So, it was a very bizarre summer, it was a time when China was the focus of global attention in a way on a kind of something that we would think of as real time following of a crisis. Not real time, like we have of minute by minute, but day by day. People would wake up, look in the newspaper and say, "What happened in China?"

Jonathan: Yeah, it was a big deal. And those stories, were then making their way back to the soldiers on the ground. So, the Marines, they were hearing from their people back home, "Oh, I just heard that all the foreigners had been killed in Beijing." And these rumors were, they were spurring them on into action. They were making them more aggressive than they otherwise might have been. One Marine, it seems according to Butler's memoirs, killed himself out of terror for what he was going to find when they got to Tianjin. Butler himself takes on this kind of Victorian, I guess, Edwardian swagger, where he's writing to his mother, something along the lines of, "And if I should die, don't be worried. I'm just doing my part to save women and children who are as dear to others, as you and my dear little brother Horace are to me," stuff like that.

And so, in real time, those games of broken telephone we're actually influencing events. And as you note, there were foreigners killed, especially at the end of 1899, to some extent in 1900. But those foreigners tended to be in the rural provinces of Xianzhi and Xiangdong, which were hundreds of miles away from where the military action was between the foreign invaders and the Qing Imperial soldiers and the Boxers who were fighting against them. Those killings were used as a pretext for the military action, even though the idea was we're going to save our precious missionaries and diplomats. They actually weren't doing anything to save them. They were just moving on Beijing basically to exert their prerogatives as imperial powers and to give the Chinese what for.

Jeffrey: Well, since your books coming out before mine, I'll draw on that in your part about the Marines, in part of what I'm writing, there's a guardian correspondent who wrote really powerfully about the sort of campaigns of revenge after the crashing of the Boxers. And he said he made this speculation, which I find really interesting that even once the rumors were disproved, there were stories that were so vivid in people's minds about this massacre of all foreigners in Beijing that hadn't happened. That was part of what spurred the allied soldiers to go about breaking nearly all the rules of war that had recently been agreed upon at The Hague. And so I think that idea that even when a rumor is disproved, if it was believed and had enough emotional power for a while, it can actually affect what happens in the history going forward.

Jonathan: Over the course of my research when I was in Tianjin, I happened on this local history that talked about the use of chlorine gun, as they call this. So essentially, chemical weapons, which were illegal under international law already at that time. Supposedly, they were used by the British, and you turn me on to a poem, that sort of back this up. There was a memory of that by a Chinese poet as well, but that some kind of chemical weapon or some kind of chlorine bomb had been used.

Jeffrey: You talked about the interconnection between these wars. I mean, by Smedley Butler being in Cuba, being in China, being in the Philippines, and there's also the connection you mentioned between this film and Westerns that were made. And in 1900, that's how people were thinking about these things as being connected. When the Boxers were being covered in the American newspapers, one thing that was brought up was similarities to the stories about what Native American groups had done to settlers on the frontier. The Boxers themselves were compared to the Ghost Dance rising.

There were some similar beliefs. There was a belief and invulnerability, and this happens in different parts of the world, in different places. When a technologically advanced foe, you sort of claim that there are some sort of spiritual techniques that can even the playing field by summoning powers, supernatural powers, go soldiers invulnerability rights. But that was part of what the discourse was at that time, and the newspapers would talk about Boxer Braves following Boxer Chiefs into battle, so there was a kind of connection between that.

And there was also an idea that there was a connection between the fighting in the Spanish American War and in China and the personnel were going from place to place. The head of the American forces in the allied army, he had been one of the heroes of the Battle of Santiago in Cuba. After the Boxers, he would go on to the Philippines. But before all of this, he had been in what were then called the Indian troubles or the Indian wars.

And so, there was a kind of connection, you we can see the American expansion that expropriated land from Native Americans was a kind of dress rehearsal for the overseas expansion that comes further. And I was really glad to see that in your book. You draw on one of my favorite recent history books on any topic, Daniel Immerwahr, How to Hide an Empire. It's not just that American involvement of the Boxer war is largely forgotten, but this whole set of interlocking forms of expansion first over land, and then across seas.

Jonathan: Yeah. So, the things that we're talking about, this is a huge event in 1900. It is a big international event. It's got everybody's attention. And then, it just disappears, basically from, I mean, if you ask people, "What is a Boxer? What is the Boxer Rebellion? Why is it even called the Boxer Rebellion?" The answer, by the way, is that they were doing martial arts and the anglophones didn't know what kung fu was. So, they just said, "It looks like they're boxing. They must be boxers."

This movie has sort of an interesting inflection point in that passage or not of historical memory. So, it's 1963. It's 63 years after this war. It had been a while, but there are people who are still alive when this movie comes out who would remember. In fact, they may have even been some veterans of the war who were still around. So, it's a movie that is transmitting this memory and it's also very much of its moment, right? So, it's 1963. It's the Cold War. The Cultural Revolution in China is still three years away. The Great Leap Forward is ending. Mao's big agricultural experiment that basically turned into a de facto genocide.

As far as most people in the United States know, China has retreated. It's essentially kind of an unknowable black hole, it's kind of the way that we would sort of think about North Korea today. The Vietnam War is happening, but escalation is just starting. And so, this movie gets made. A lot of money went into it. It was a $10 million movie, which is a pretty big budget in 1963. It flops at the box office. It just sort of makes back what they put into it. But the biggest movies of that year were Cleopatra, starring Elizabeth Taylor and the number two movie was How the West Was Won directed by John Ford, who, by the way, also came on set for this movie to advise at various points along the way.

And so, this Hollywood studio, they're like, "Okay, we need to make a Western, we need to make a movie about China. We're making a movie that's looking backward across two world wars. And we're making a movie that's really at the height of the Cold War." We're just removed from the Cuban Missile Crisis. I guess what I'm asking is, what do you think the point of this movie was? Why did they make it? And do you think there's anything about this movie that is part of the reason why the Boxer crisis doesn't get remembered in the 60 years since it came out?

Jeffrey: So, I think, I mean, I just pushed back a little, compared to most other events in Chinese history, people do have at least a vague sense of it, they recognize the name. They're not just one, but two rock groups called the Boxer Rebellion. And it lives on in this kind of strange, half remembered way, that I think, in a way that the Taiping Rebellion or Taiping uprising in the middle of the 19th century. Much, much bigger death toll, not as much involvement of foreigners, but some involvement of foreigners, it was a very big event at when it took place, but has now been really, really forgotten as most events in China. It just don't resonate outside of the West.

But the Boxer Rebellion because it has a kind of catchy name to remember and things like that, so it lives. There's a Buffy the Vampire Slayer episode that has a kind of flashback to Beijing in 1900. So, it has this curious kind of half-life, it does stay on, but it's only very imperfectly remembered. So, for the time when the movie was made, the director or the writer did mention that one of the things that kind of intrigued them was that it was an example of international cooperation the way that the UN was supposed to do but kind of wasn't, so they were intrigued by all these different foreign powers getting together.

And actually, my favorite scene probably is one where you have the different foreign contingents are each playing their own national anthem or different songs. And so, you just hear this kind of what starts out is as different national anthems but it quickly becomes the kind of cacophony. And one of the Chinese characters in the film just says, "This western music, it's really terrible." It's great, because it's kind of a play on the fact that Westerners so often think of Chinese music as discordant, but there was this kind of discord going on.

Jonathan: And I believe that those are also white people in yellow face. But one of them says they're all saying the same thing, "We want China."

Jeffrey: Right, right. It's very interesting that way, and there are bits and pieces of Cold War, that show through. The Japanese doesn't have a big role, the Japanese diplomat, but he comes across relatively well in a way that 20 years before this, they were making films in which the Japanese had to be the enemies and the Chinese were the heroes because you had the alliance. So, there's a kind of flexibility there.

Jonathan: And as you noted, so that the producer describes that, what they're trying to do here is they're trying to express this international ideal, that's kind of, the UN, it's the high Cold War, but it's also the high days of idealism of the United Nations or what the United Nations could be. I think it's notable. So, you were talking about that that seemed at the beginning, when everybody's playing their national anthem.

It's interesting that the first national anthem that you hear is the Russian national anthem. But then you see the Russian flag, which happens to be the current Russian flag, but at that point was anachronistic, right? Or not, I mean, it was it was appropriate for its time, but it was not the flag that was being used in 1963. It's what is now the flag of the Russian Federation.

A lot of the plot has, it's sort of about Charlton Heston as the rootin’ tootin’ American militarist marine. He's sort of what Smedley Butler imagined himself to be when he was 19 years old. He's the cowboy on the frontier. And then David Niven as the erudite or bane British diplomat. And they have a scene toward the beginning where Charlton Heston is basically like, "These people are going to come and kill all of us. We have to kill all of them first or defend ourselves or get out of here," or whatever.

And David Niven keeps talking about principle and how, and throughout the movie, he's saying that it's easy to fight over a piece of land, it's hard to fight for a principle. And the only principle that I could figure out that he was talking about was sort of this international ideal that perhaps all of the all of the "civilized countries" in the world could come together and not start World War Three, essentially.

But because it's done under the rubric of a Western, and also, it's coming out of the larger culture that produced both of those, it seems like what this principle is and what this movie represents is sort of the civilized mostly white plus Japanese nations coming together against barbarism. In the same way that in Fort Apache it's John Wayne and the cavalry against the Indians. And David Niven even at one point, he makes a direct parallel, right? He says, "You can't just go around shooting Chinese the way you shoot Red Indians in your own country." But it seems like sort of the idea is that civilization can come together against a threat. And that threat is the scary, barbaric Chinese who are shot from below and they have the long alien fingernails and they just look and sound really weird.

Jeffrey : In that parallel, also Teddy Roosevelt in 1900, did directly say, "If you think we're wrong to be going against the Boxers, what do you think, we were wrong to move against the Apache when they were on the warpath?" This is carrying over of that things. But there's one other part of the movie that is based in history. It's given a particular spin that I think is worth mentioning, which is that when the Empress Dowager is trying to decide how to deal with the Boxers, because there are two members of the court who are close to her. And one of them is arguing, which is clearly a villain of this Prince [Duan 00:33:24] is saying, "We've got to work with the Boxers because we need to push back against the foreigners." But another is arguing differently and has a more kind of cultured persona and voice. They're both white actors playing in yellow face.

Jonathan: The good one is British and speaking sort of with a received pronunciation.

Jeffrey : Very refined. Yeah.

Jonathan: And Prince Duan is played by an Australian character actor, who I think probably was, and they definitely lean into this, he definitely reads as gay on screen, which in 1963, I think is meant to signal sinisterness, untrustworthiness. His makeup is heavier. The movie is trying to show kind of this good Chinese figure and the evil one, and the evil one is winning that contest.

Jeffrey : Right. And you could think about, I mean, this is playing into the Cold War side. You could think of it like the one who wants to be more cooperative with the West and loses the struggle with the Empress Dowager over this policy. You could think of that as representing say, Taiwan at that point under Chiang Kai Shek, if you want to think about it. With China, there's often been in the American imagination. There is a good China that we could be allies, whether we have been allies with them, and there's a bad China that we're sort of at irreconcilable odds with. And clearly at that point, the People's Republic of China was beyond the pale representing the China that we can't deal with.

Although, by the time of Deng Xiaoping, there's a period of a kind of romance of the idea of the possibilities for engagement where hopes are invested in him. So, I teach the film most often in a kind of US China class and things like that. And it's of a particular moment where it was a low point in US China relations, and we're in another low point.

Jonathan: The racism in the movie, which you definitely could not get away with in 2022, you also couldn't have probably gotten away with it just a decade or two after this movie was made. So, this comes out in '63. So, the Hart Celler Act, the big Immigration Reform Act, which is in a lot of ways, itself a product of the Cold War. At the time that this movie was made, we're sort of at the end of the decades of the Chinese Exclusion Acts, where US policy is essentially that Chinese people cannot immigrate to the United States. And the Asian people, more generally, there are some exceptions, the paper names and you have immigrants who are pretending to be members of families that are already here.

But it's two years after this that really the doors are opened, and most Chinese Americans, Korean Americans, Vietnamese Americans, most Indian Americans, most people from Asia, whose ancestry is from Asia recently who are in the United States now, come as a result of this law that is passed two years after this movie comes out. In the movie, one of the subplots is the half Chinese, half Anglo daughter of one of the Marines who's killed in the movie, the end of the movie, when Charlton Heston basically rides off into the sunset, he rides off with her. And sort of earlier in the movie, there's this discussion about whether this Marine should take his half Chinese daughter with him to Illinois, and Charlton Heston is like, "Are you crazy? They'll look at her like she's a freak. She's better here with her own people."

And there's like, there's some self-awareness that America is racist against people from Asia, Chinese people, people of Chinese descent, but obviously, not enough awareness that would then keep the makers of the movie from casting all of the major Chinese roles as white people in heavy alien makeup. I don't know. I should ask you maybe like that. What are your students think of that when you show them the movie? How did things like that read today?

Jeffrey : That is very dated. I've thought a lot about the Exclusion Act and where it fits into this story. I think of it partly because five years after the Boxers are crushed, there's a boycott movement in China to try to push back against the exclusionary act and get it overturned. And it's a non-violent boycott movement. But what happens is that the Americans tried to discredit it by saying, "Oh, this is just Boxerism again." There's a way in which this kind of the Boxers become this specter that can be raised by whichever imperialist power is being threatened by a popular movement, even when it's a non-violent popular movement. But the specter of the Boxers gets raised again in the 1960s during the Cultural Revolution, where the Red Guards actually do threaten diplomats at one point in this kind of heyday of anti-foreignism during the Cultural Revolution.

But at that point, in the time of the anti-American boycott in 1905, the response is, "No, we're nothing like the Boxers. They were xenophobic and they used violence." We're just trying to get justice and we're using non-violence. By the Cultural Revolution moment, Mao and as far as you're saying, well, the Boxers actually were heroes. We shouldn't try to distance ourselves from the Boxers because after all, didn't they have right on their side in the sense of being against imperialism, even if they didn't have the benefit of scientific Marxism so they could succeed. Still, we should think about them as something to admire.

So, around the time of this film, another thing to say is this is the biggest divide between the way the story of the event is told inside China and outside of China. Because in 1960 itself, the 60th anniversary of the crisis, there's enormous outpouring writings about the Boxers in China because 60th anniversary is in traditional calendrical systems, it's almost like a centennial in western timekeeping. And under Mao, the Boxers were being seen as heroes. So, there were tons of academic books and nonacademic books being published and a whole series of comic books were put out to try to convince young Chinese people to think of the Boxers as heroic figures. So, you have the totally opposite view of the event going on in 1960 within China as this film is being dreamed up for Hollywood.

Jonathan: Yeah, yeah. I'm guessing this movie was not shown in Mao's China. I mean, do you know how this movie has been received since?

Jeffrey : So, I don't know about this film being shown then, but during the Cultural Revolution, there was so much of a kind of identifying Mao of the Red Guards with the Boxers and Mao to some extent with the Empress Dowager in a strange way. That there was actually a call for public condemnation of a Chinese language of film, Secret History of the Qing court, which because it portrayed the Boxers not heroically enough.

Jonathan: Yeah, it's really interesting. And when I was in China doing research for Gangsters, there was a lot of memory of the Boxers that was preserved in this heroic way. The Dagu Fort Ruins Museum, which was the place where Smedley Butler and the Marines and most of the foreign troops first came ashore in 1900 at the mouth of a Haihe River. And I ended up at the Boxer Shrine and there's people doing exercise, sort of trying to recreate in sort of a slow motion Tai Chi style, like the methods of the Boxers. This is still remembered in China today as a as a heroic event. Totally opposite of the portrayal that's in this movie of essentially just a bunch of barbarians who fall over themselves and then all end up getting killed, and then the dynasty falls.

Jeffrey : Yeah, I think there's been a shift in post Mao China, while there are places where there's this has kind of kept alive and the heroic vision. In general, there's a bit of a discomfort with the Boxers, because they were also anti technology and can be to easily flow into this kind of superstitious or [inaudible 00:42:52]. But there's a very strong memory of the catastrophe of the invasion and the injustice of the Boxer protocol. The treaty that was signed in 1901 right after a period when lots of people on all sides had behaved really abominably. But the treaty just said that foreign countries could get an indemnity for the loss of foreign lives and property. And there was nothing done to try to hold the foreign armies to account for the looting, the destruction of villages.

I mean, and just to give you a sense of scale, in October of 1900, German historian has estimated the German troops alone destroyed 20 villages in China. And that was just in one month and one set of troops. So, what's remembered in China now very broadly is that 1900, 1901 was this period of the [inaudible 00:43:51] eight allied army invasion and villainy. And so, in the Mao period, you talked a lot about the heroes of the Boxers, and then these comic books, that would be this strong Boxer hero who would win a great victory even though in the end the movement didn't succeed, you were trying to remember them as heroes. Now it's more, the Boxers they had a justified reason because they wanted China to be protected under Chinese control, but don't talk too much about them siding with the Manchu Qing Dynasty, which some movements saw as outsiders but they were loyal to it.

But what you really focus on is, this was used as a pretext for in a sense of military occupation that then lasted for many months and caused a great deal of suffering. When you grew up in America, in my generation, you learned about the Red Coats. You learned about this group that stood for people who were on your soil doing bad things. And there are all kinds of things that are remembered or not, but I thought about that, What does it mean if the only violence that we remember taking place in China in 1900, to the extent we remember at all, is Boxers killing Christians, when you also had all of these actions of foreign soldiers killing Chinese people?

Jonathan: Right. Right. And I mean, and that's one of the things that stuck out to watching this movie. It had been 60 years since the events but trying to imagine a movie about World War Two even 50, 60 years after the end of that war. That just got all of the actual military details just completely wrong. I mean, it was almost as if somebody was trying to make Inglourious Basterds, but Solden is an accurate depiction of how Hitler had died in 1944 in a movie theater in Paris, right?

It relies, Nicholas Ray, the director, who has a heart attack, or like some kind of tachycardia early on and he had to drop out of the production and they brought in two others. And that's part of the reason why it was a sort of a conceptual mess as they were putting it together. But they were, they were sort of untethered from the need to have any kind of fealty to historical accuracy. Because the eight-nation allied army is not an important part of Americans historical memory of themselves or the major historical memory of the West.

It is just sort of like, "Oh, a thing happened in China. Some people died. There were some battles. There was a siege. There were some troops who were moving 70 miles from the coast to Beijing." I remember all that. Just sort of put all that in the food processor, put it on high, and then you end up with this movie, which would be a very hard thing to do about an event that people remember in more detail, like World War Two or Vietnam.

Jeffrey : Yeah, I think that's a good point. And I mean, they're just playing fast and loose with things. And it's us also, getting back to this kind of idea of a UN vision of this, I do think of the Allied Army as being a kind of precursor to things like UN peacekeeping forces. And like those peacekeepers, they sometimes get involved in doing things that are very different from their alleged civilizing mission. But one thing about these international stories...

Jonathan: As I know very well from firsthand experience, yeah.

Jeffrey : You know very well, but I think it's also interesting that the way the story is told, who you put at the center, but I mean, so even though it's an international story, there's Charlton Heston is clearly who you're always supposed to place at the center, an American. And the British during the event, they would think of the center figures in it being British and there was a German story of it as well. So even in these global moments, I think what's very interesting is they get fed through also a very nationalistic lens, even when there's an internationalism to it, it's part of a national story and national myths.

And one of the national mess that that Americans have tried to cling to is not being an empire building kind of country. So, you can see why things about the allied army, I mean, the American government didn't want a formal colony in China, but there were also plenty, there Americans who said, "Yeah, well, we need an island like the British got Hong Kong. Maybe we could get Hainan island, which is in between the Philippines and China. And a lot of the discussions of the Philippines was the value of having a strong presence to the Philippines, it would be a stepping stone to China or at least be access to the market.

So, these are all part of that milieu. So even when it was an international effort, it was also fed through these national rivalries that were just being kept partially in check, and there was actually worry at the time. China was seen as too big a prize for any one of the foreign powers, to get it would offset the balance. But there was worry that at some point, there could be a big international war fought over control of China if these countries that were tenuously cooperating stopped being able to cooperate. And in some ways, this isn't that far off. There were predictions that maybe even though Russia and Japan were part of the allies, soon they would come to blows over competition for influence in Northeast Asia.

Jonathan: Which of course they did.

Jeffrey : Exactly what happened.

Jonathan: Exactly.

Jeffrey : So, that's what happened. So, there are ways in which the Boxer crisis to me seems it's a harbinger of things to come.

Jonathan: And in a lot of ways, I mean, most Americans wouldn't think about it this way, but there was a war fought between powers over control of China. It was called World War Two. I mean, Japan and the United States, that was main part of what we were fighting over. It's interesting in this movie. So, Nicholas Ray, the director, and by the way, this movie ruined his career. This was the last major feature that he directed because it did so poorly at the box office. Charlton Heston said that his takeaway from the movie was never film a movie without a finished shooting script before it starts.

But Nicholas Ray, and I assume this is after his heart attack thing, he actually makes a cameo in the movie as the US minister. And in the scene, where all of the ambassadors basically are deciding like should we stay or should we go, and they're all like, we should go. And then David Niven is like, "We should stay." And then they're all like, "Well, you're the British guy. You sound like you know what you're talking about. We should stay." Nicholas Ray, he has this cameo and they made sure to put in his mouth this line that, "The United States has never wanted any kind of territory in China, never will."

Sir Arthur Robertsen (David Niven): We need your vote on whether to stay or leave Peking.

U.S. minister to China (Nicholas Ray): The United States has no territorial concession in China. Never asked for and don't want one. I'm afraid I've to abstain, Sir Arthur.

Jonathan: That really goes to the heart of the American self-story about ourselves as an empire, that is not an empire.

And China was a place that was very formative in that because as people might remember from their high school US history classes, the reason why the United States was arguing for an open door trading policy in China, where no nation would dominate was because we knew in 1900, that we weren't going to be able to defeat the Brits, and the Russians and the French, and kick them out of China and make China a colony for ourselves. So, we needed as a place to share.

But were very convinced that it was a place where white people especially English speakers, should dominate. And so that was very much in the thinking that was behind the pressure that was being put on then President McKinley. And then later, he didn't need any pressure, because he just had these thoughts himself, Teddy Roosevelt basically make China our play thing to the greatest extent possible, as long as it didn't then get us involved in a world war against the British or the Russians or whatever,

Jeffrey: My students, my family have certain drinking games about these topics I have to bring up no matter what the topic is, and one of them is Mark Twain. So, Mark Twain was one person who didn't buy this idea and actually thought that the United States was more similar to these other countries than different and his last writing of the 19th century was the salutation from the 19th century to the 20th. And he talked about how the century was ending with Christendom, besmirching its reputation around the world through pirate raids. And he said, and in South Africa, in the Philippines, and in China, he used different terms for each one. So, he was basically saying, what the British are doing formally an empire in South Africa and is not that different and is reprehensible in the same way than what the United States wants to be doing in the Philippines and what all the groups are doing together in China.

Jonathan: And Mark Twain plays a big role in bringing attention to the looting that the foreigners including, by the way, Smedley Butler engaged in China during the Boxer war. And there's sort of a sideways reverse nod to that at the beginning of this movie, when Charlton Heston in his opening monologue says, "This is like anywhere else. You have to pay for pay for anything that you want. Don't tae things that don't belong to you." Which is not what the Marines were saying to themselves. We need to wrap up briefly, what do you think? Thumbs up or thumbs down? Do you recommend that people go watch 55 days at Peking?

Jeffrey : I'd say it's a great opening sequence. I mean, in different way, you can get a lot of the things that are interesting out of the movie out of the first 15 minutes or so including this sort of beautiful watercolor start. So, I think maybe thumbs down, but maybe, do some fast forwarding through it. Look at the beginning. Don't get hung up on the love story. So, yeah, I'd say it's of historical interest.

Jonathan: I think it's yes. It's of historical interest as a document. I think it's worth watching. As a movie, it is not a good movie, even if you need to watch a super, racist Western from the period. I would recommend most movies by John Ford and John Wayne over this one. I think this one didn't make it at the box office for a reason, but it is an interesting historical document and sort of a good cringe watch, if you need [crosstalk 00:55:36].

Jeffrey : Exactly, exactly.

Jonathan: Thank you very much, Jeff. I really appreciate it. I think I learned a lot and I hope everybody else did too.

Jeffrey : That's great. I got a lot out of it, too. I learned some great tidbits. Thanks a lot.

Jonathan: Jeffrey Wasserstrom is a professor of modern Chinese history at the University of California, Irvine. So, as I said at the top, this is pub week for Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, The Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America's Empire. Please buy the book.

On January 27th, at noon, Eastern Time, I'm going to be doing another online event. That one is going to be hosted by New America. And that one is going to be me in conversation with Clint Smith, the freshly minted number one New York Times bestselling author of How The Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America. It's on the top 10 list of all the books of 2021. It's a terrific book. And our books actually have a lot in common. Both of us traveled to and explored sites of memory of eras whose memory has been largely suppressed and sanitized. So that's going to be a great conversation as well. More information about the Clint Smith event at newamerica.org/events.

Our next Racket podcast is going to be another Gangsters Movie Night. This one is going to be about a movie about the Philippine American war in which Smedley Butler served. It's also going to be our first non-American made film and the first movies specifically referenced in Gangsters, 2018 Filipino epic Goyo: The Boy General. It is also, I can confidently assert the only movie we'll be talking about in which I personally made an appearance. We're going to be talking about that with Filipino film critic Philbert Dy, who will be joining us from Manila. It's going to be great.

Sign up at theracket.N-E-W-S or hit the subscribe button at Spotify, Downcast iTunes, wherever you listen to podcasts so you don't miss it. While you're there, please leave us a review. It helps people find us. Thanks to The Racket podcast team. This episode was produced by Evan Roberts, Annie Malcolm and Sam Thielman. Our theme music is by Los Plantronics. Thanks for listening. Stay safe. Buy Gangsters of Capitalism. See you next time.

Share this post